Article by Sara Simeone – Consorzio Materahub

Depopulation of rural areas, caused by a combination of population loss and population aging, keeps hindering their socioeconomic development.

This complex social problem caused by emigration and brain drain, decreased birth-rate, population aging and consequent depopulation, varies in scale and scope according to the village or area.

One of the main reasons for abandonment is the unsatisfactory level of wellbeing found in many rural and marginal contexts in a ‘downward spiral’ (Salvati, 2011) which progressively makes them less attractive, impoverishes the human resources present and, consequently, the possibilities for economic and social development.

One of the other consequent issues is that the Utilized Agricultural Area (UAA) keeps contracting, for instance in Italy it reduced by 14% from 1990 to 2010, impoverishing the agroforestry system.

In this scenario, quality of life is a preliminary condition to initiate processes of endogenous territorial development.

SOME OF THE POLICIES ENACTED SO FAR IN EUROPE AND ITALY

Several methodologies and strategies have been developed in the last decades for sustainable rural development, or, as defined by the European Commission, Territorial Innovation Models, such as the Community-Led Local Development (used for the ESI Funds) adopted by the EU in the 2014-2020 programming period.

As for the policies enacted in the last decade to face these complex challenges, there is a new orientation in support of rural areas, including economic diversification, not limited solely to supporting production activities. To this regard, the Cork 2.0 Declaration should be mentioned, with its emblematic title A Better Life in Rural Areas, as well as the Common Agricultural Policy, which both align with the objective of rebalancing the territorial development, by promoting viable farm income, attraction of young farmers, environmental sustainability, business development and general wellbeing in rural areas.

Moreover, the United Nations also state that rural areas play a key role in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the Italian National Research Programme, based on Horizon 2021-2024, aims at improving rural well-being and long-term socio-economic prospects, along with mitigation of climate changes. One of the expected impacts of Horizon 2021-2024 is to develop rural, coastal and urban areas in a sustainable, balanced and inclusive manner thanks to a better understanding of the environmental, socio-economic, behavioral and demographic drivers of change as well as deployment of digital, social and community-led innovations. The National Recovery and Resilience Plan for Italy also pursues social and territorial cohesion through a set of investments.

Concerning the evaluation of quality of life, due to the multifaceted and complex nature of this concept, policymakers may encounter difficulties in identifying and evaluating the individual, social, material (income, housing, infrastructure, etc.) and non-material (spirit, psychology, cultural quality, etc.) components to intervene on.

MEASURING QUALITY OF LIFE: WHY SO IMPORTANT?

To evaluate and improve quality of life, we should talk numbers, but GDP proved no longer enough for this purpose.

Two examples of composite indicators developed to measure quality of life are the Human Development Index (HDI), based on Sen’s Theory of Capabilities (1992) and calculated annually for 187 countries by the United Nations Development Programme, and the Better Life Index, which compares wellbeing across countries based on 11 dimensions that the OECD has identified as essential in the areas of material living conditions and quality of life.

Sen’s Theory of Capabilities (1992) gives a framework to define wellbeing and argues that the quality of life does not derive from the possession and/or consumption of goods and services but, given their availability, it is the expression of what people are able to be and do, according to a concept of freedom of choice. This theory led to the development of statistical indicator systems and becoming a reference point in evaluating quality of life in the EU.

There exist also spatial models based on a combination of objective and subjective data collection, allowing to make comparisons over the years.

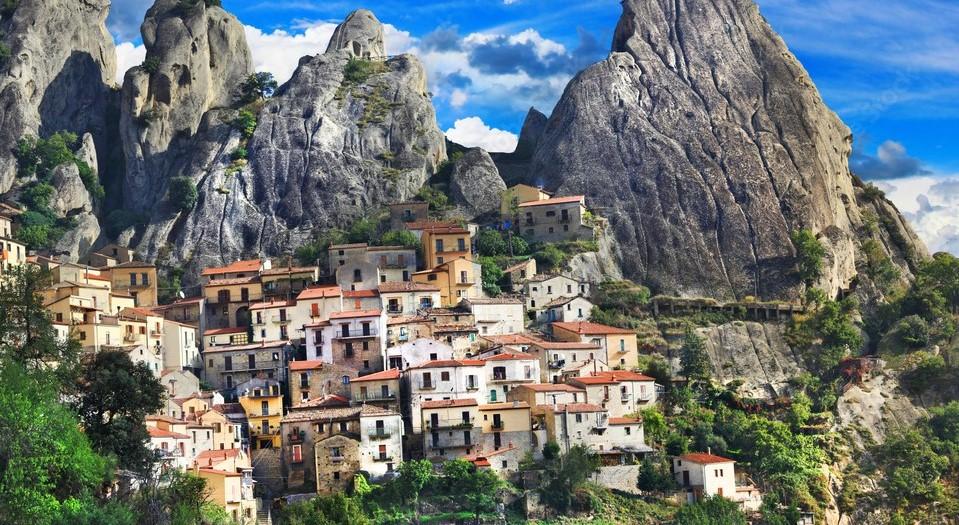

Such models allowed to discover, for example, that in the Italian region of Basilicata, from 2001 to 2011, the Quality of Life indices record a raise in work, education and training, and a decrease in Research and Innovation.

In Basilicata, the most marginal municipalities are those with a greater ecological value, but the progressive abandonment of these areas could undermine the safeguarding of natural environments and associated ecosystem services (see source: Viccaro et al., 2021).

Some scholars use further surveys to gather micro-data and verify more in detail the local specificities.

Some others also want to enlarge the dashboard of indicators with qualitative and subjective indicators (e.g. on work, health care, landscape and cultural heritage, environment, etc.), like Casini et al. (2021), who ask their interviewees for an effort to provide an overall evaluation, for their municipality of residence, of the level of satisfaction of their community with quality of life, because abundant literature proves that “the global satisfaction with one’s community” is what counts in the end.

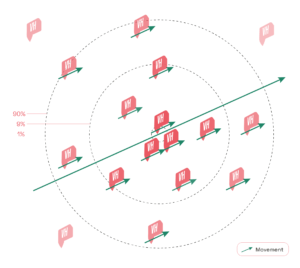

THE POTENTIAL SOLUTION: COMMUNITY RELATIONSHIPS AS A CATALYST FOR AN UPWARD SPIRAL

This is why, opposed to the ‘downward spiral’ we need to trigger an ‘upward spiral’. An improvement will attract another improvement, and so on and so forth.

To solve such a complex and root problem as depopulation, there is the need to start from the revitalization of local communities, by building, consolidating, and favoring the cohesion of the social capital.

Nevertheless, strategies that start from community as a catalyst have rarely been devised and implemented.

This complex problem needs collaborative processes for collective impact as theorized and demonstrated by Kania and Kramer (2011), aimed at reconstituting the socio-cultural asset of countryside capital and strengthening relationships which consequently foster innovation, knowledge exchange, business development and overall quality of life improvement in rural areas.

Some opportunities for improvement are represented by trade Local Action Groups or Unions among Municipalities and by fostering processes of endogenous development in the rural areas.

For example, collaborative processes can have an impact also on the provision of, among others, employment or healthcare services. The former, for example, can be provisioned with substitutive services like health services ‘at the doorstep’, overcoming the distance of health infrastructure; the latter can be tackled with new working and company management models such as remote working (Barca, 2014). Of course, the scenario is much more complex and needs to be thoroughly analysed.

Such collaborative processes for collective impact need to be contextualized, studied and analysed in order to elaborate a strategy for social capital revitalization in rural contexts based on social interrelations, overcoming the choice between endogenous and exogenous development, and following a nexogenous approach instead.

SOURCES

Barca, 2014. https://www.miur.gov.it/documents/20182/890263/strategia_nazionale_aree_interne.pdf/d10fc111-65c0- 4acd-b253-63efae626b19

Benayas, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1079/PAVSNNR20072057

Bock, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12119

Carrosio, 2022. I dispositivi abilitanti per una politica di sviluppo place-based.

Casini et al., 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1978-0.

Casini et al., 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.01.002

Chiodo, 2019. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020432

European Commission, 2007. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2777/24171

European Union, 2016. doi: 10.2762/011384 European Union, 2017. doi: 10.2785/021270

European Commission, 2021. Cohesion Policy 2021-2027. Eurostat, 2020. https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ef_m_farmleg&lang=en

EU SCAR, 2012. https://scar-europe.org/images/AKIS/Documents/AKIS_reflection_paper.pdf

Garrod, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.08.001 ISTAT, 2019. https://www.istat.it/it/archivio/236714

Kania and Kramer, 2011. https://doi.org/10.48558/5900-KN19

Mazziotta and Pareto, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1577-5

Salvati, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.07.030.

Sen, 1985. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232999

Stiglitz, 2009. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/8131721/8131772/Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi-Commissionreport.pdf

Stiglitz, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264307278-en

Viccaro, 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105742